Guest Post by Eric Kuhnen (President, GlobalLink CCMS)

“Theory of Operations” Content Is Worth Writing

Among all the kinds of technical documentation that can be written, a Theory of Operations document stands out as one that should be prioritized. Moreover, if crafted effectively, it will be read and utilized. This assertion is backed by both practical experience and research—but first, let’s define what it is.

What Is “Theory of Operations” Content?

A Theory of Operations document explains how a product, system, or component is intended to work. Where applicable, it includes the scientific principles underlying the subject being described.

To understand its purpose, consider the various types of users:

- Naïve users: Have little or no understanding of a system—its purpose or operation.

- Novice users: Have some knowledge of the system’s objectives but lack operational expertise.

- Competent users: Understand the system and its use.

- Expert users: Operate the system automatically and intuitively.1

This document bridges gaps for these user types by providing crucial foundational knowledge.

Key Components of “Theory of Operations” Content

While no universal standard governs the structure of these documents, most examples share two core components:

- Purpose Statement: Explains why the product exists. For instance, a document about a flashlight might state, “The Rayovak model 1234 flashlight is designed to provide economical, portable light for inspection, maintenance, and repair activities in poorly lit environments.”

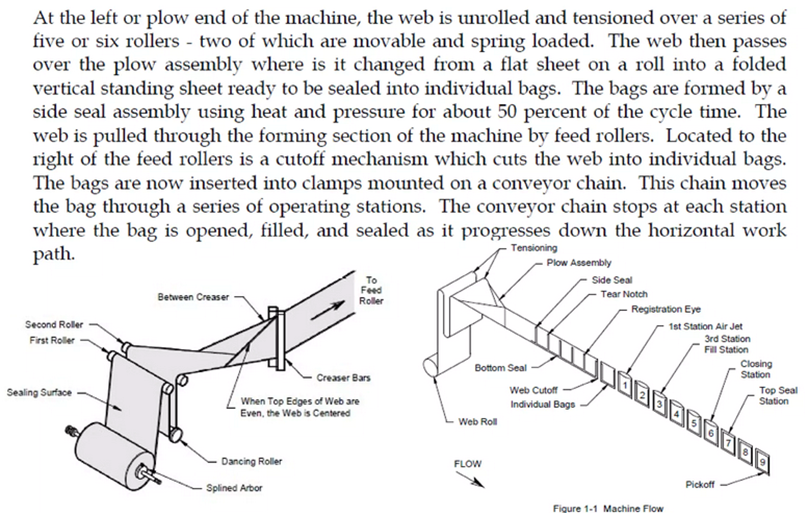

- System Overview: Details the main components and their relationships, often illustrated with images and explanatory text.2

Why Write “Theory of Operations” Content?

A Theory of Operations document consolidates general knowledge, helping readers make sense of the scattered information typically found in procedure manuals and reference guides. It’s an invaluable tool for knowledge transfer, as highlighted by Chris Justice and Melissa Nickel in their 2020 article:

“The Theory of Operations is one of the most effective tools to provide knowledge transfer, and one of the least used. The Theory of Operations is not as detailed as CAD drawings, Schematics, or Source Code but provides a condensed description of how the detailed design works. While a theory of operation can’t be provided to a machine shop to order dimensionally accurate parts, a theory of operations helps capture the underlying engineering rationale and the math that makes complex technology systems work. Countless hours are invested in discovering effective methods to accomplish product goals, with many promising dead-ends explored, and some accidental discovery of non-obvious factors. The theory of operations is where all this knowledge should be captured – what works and what didn’t. The theory of operations describes how a product works and why it works. It doesn’t provide part prints for fabrication, but it’s the product’s technical handbook, written for an audience of other engineers.”4

These documents:

- Archive discoveries, including both successful methods and dead ends.

- Offer engineers a technical handbook to understand “how and why” a product works.

- Serve as a bridge for naïve and novice users to become competent and eventually expert users.

Roy L. Chafin noted over 40 years ago:

“The naïve user needs to understand the system’s context, functionality, and operational details. A Theory of Operations document provides the semantic knowledge to meet these needs.”

In short, this type of document captures vital intellectual property that is typically absent from standard user guides or manuals.

People Will Read Well-Written “Theory of Operations” Content

Since 1982, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has tracked trends in literary reading (novels, poetry, plays). Their findings indicate a decline in reading for pleasure.5 However, reading for work presents a different trend.

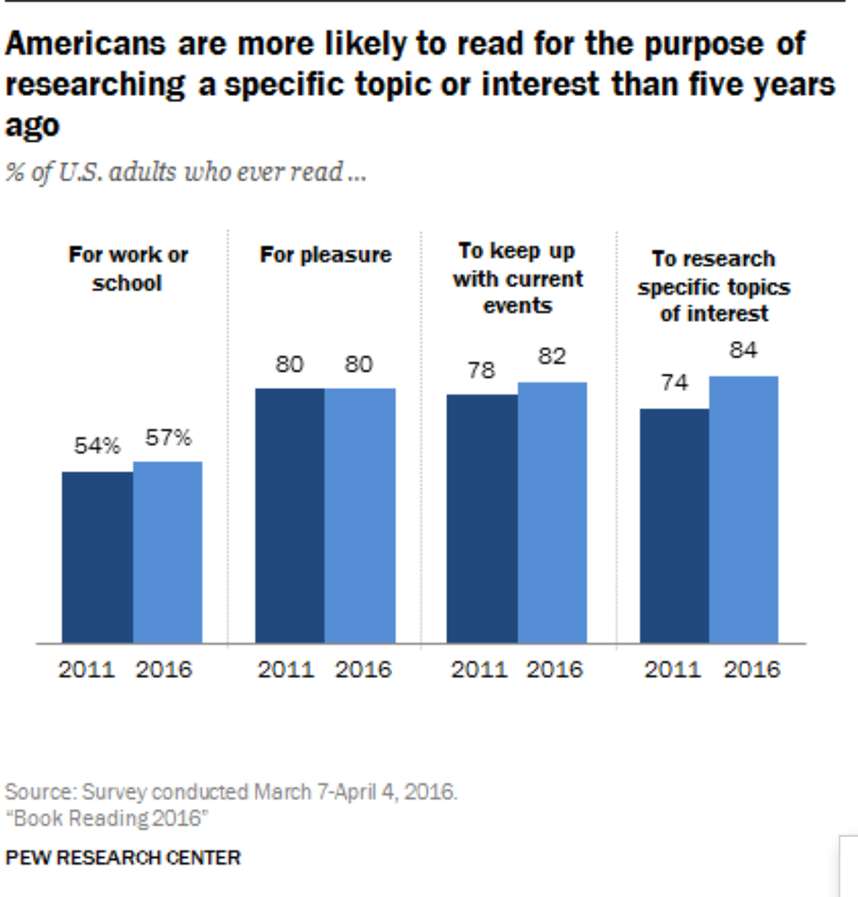

The Pew Research Center conducted a phone-based survey in 20166 to assess book-reading habits. Their findings reveal:

- While pleasure reading remains unchanged, reading for non-leisure purposes has increased significantly.

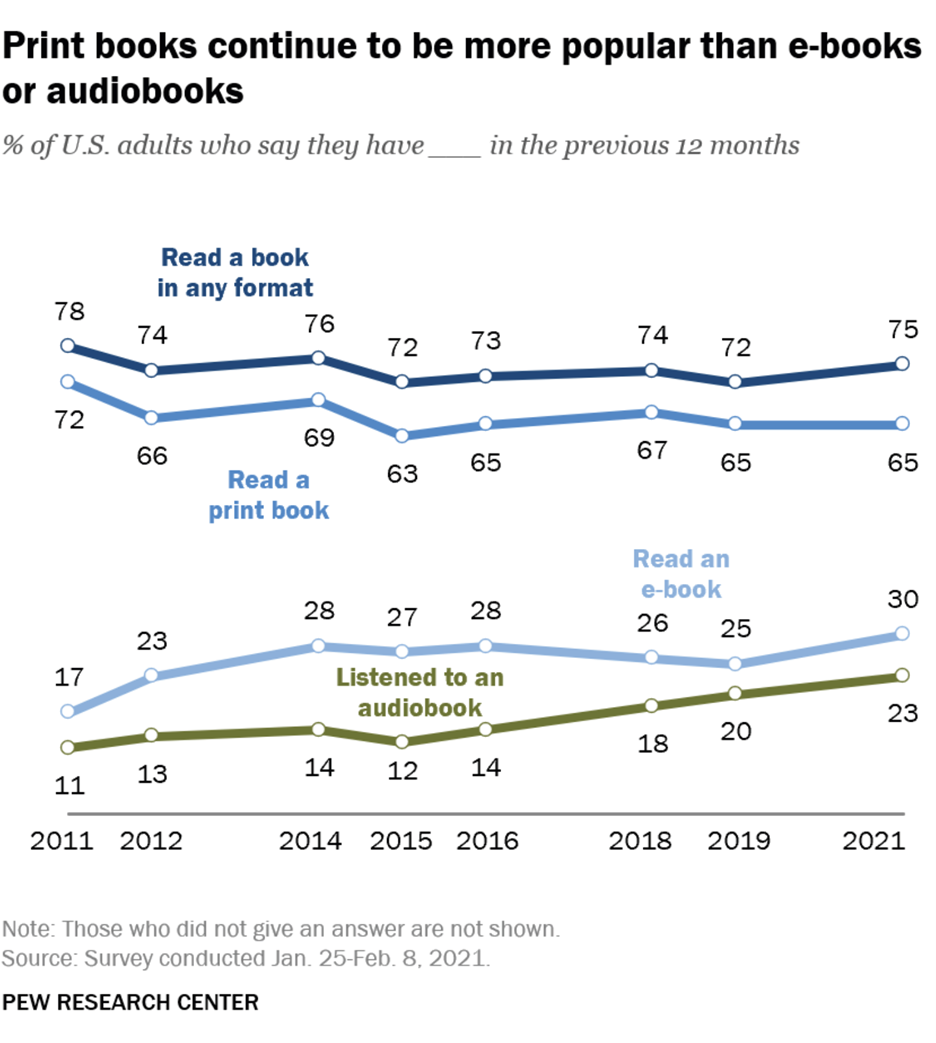

- A 2022 update confirmed this upward trend, particularly for work or research-oriented material.7

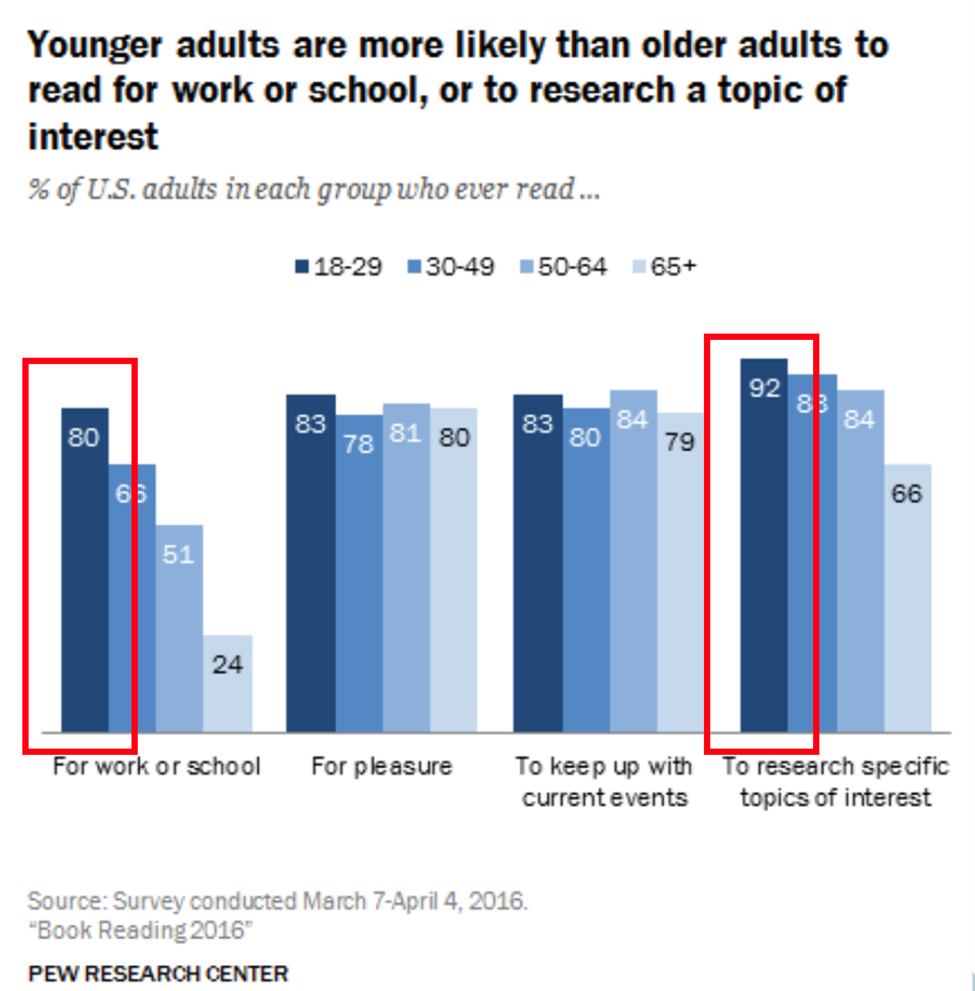

- Younger adults (ages 18-29) read work-related or research-specific materials at higher rates than other age groups.

- Following a 2019 study, the share of Americans reading e-books has increased from 25% to 30%, while print and audiobooks remained steady.8

Conclusions

- A well-crafted Theory of Operations document preserves critical intellectual property and accelerates user competency.

- Reading for work-related purposes is increasing, contrary to the decline in leisure reading.

- If you write a good Theory of Operations document, people—especially younger professionals—will read it, ensuring effective knowledge transfer and improved system understanding.

References

1 Chafin, R. L., “User manuals: What does the user really need?”, ACM Internal Conference on Design of Communication, January 22, 1982; retrieved from https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/800065.801307.

2 From “Theory of Operations_rev_02” by Keith Johnson, June 7, 2016; retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/theory-of-operationsrev02/62832112.

3 Ibid.

4 Retrieved from https://engenio.us/news-and-insights/preserve-technical-knowledge-accessible-documentation/.

5 See “Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America”, National Endowment for the Arts; 2002; retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/RaRExec_0.pdf.

6 “Book Reading 2016”, Pew Research Center; September 1, 2016; retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/09/01/book-reading-2016/.

7 “Three-in-ten Americans now read e-books”, Pew Research Center; January 6, 2022; retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/06/three-in-ten-americans-now-read-e-books/.

8 “Three-in-ten Americans now read e-books”, Pew Research Center; January 6, 2022; retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/06/three-in-ten-americans-now-read-e-books/.